((( Sharing The Stories Of The Cairngorms National Park )))

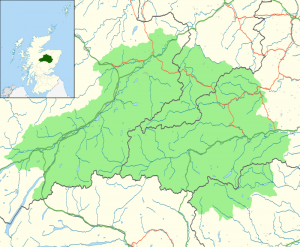

Scotland’s largest national park has produced a guide to interpretive planning that is both a cause for celebration and a reason for alarm. The celebratory part comes from the park’s decision to invite everyone dealing with visitors to become an integral part of its plan. The alarm bells start ringing with the realization that there’s not much actual interpretation in its guide. Basically, what’s been produced is a kind of economic development piece focused on building a brand, with some random interpretive ideas interspersed among its pages. Although the cover states it is “a guide to interpreting the area’s distinct character and coherent identity,” that’s misleading. It’s really a loose framework for those involved with visitors to interpret the area for themselves, then share whatever they come up with, just being sure to call the place a park and mention its mountains. Other than that, they’re on their own. This is the kind of approach that is likely to be widely adopted elsewhere, because it requires so little in the way of staff and resources. Everyone interested in interpretive design should take a close look at it. (It is available on the internet.) I am grateful to the authors that shared it with me. Although I feel strongly that they missed the mark in interpretation, I can appreciate the time they spent in laying out their position and rallying people around it. I wish I could be more positive about their results. The guide is organized around four “key themes,” which supposedly “define” the park:

Scotland’s largest national park has produced a guide to interpretive planning that is both a cause for celebration and a reason for alarm. The celebratory part comes from the park’s decision to invite everyone dealing with visitors to become an integral part of its plan. The alarm bells start ringing with the realization that there’s not much actual interpretation in its guide. Basically, what’s been produced is a kind of economic development piece focused on building a brand, with some random interpretive ideas interspersed among its pages. Although the cover states it is “a guide to interpreting the area’s distinct character and coherent identity,” that’s misleading. It’s really a loose framework for those involved with visitors to interpret the area for themselves, then share whatever they come up with, just being sure to call the place a park and mention its mountains. Other than that, they’re on their own. This is the kind of approach that is likely to be widely adopted elsewhere, because it requires so little in the way of staff and resources. Everyone interested in interpretive design should take a close look at it. (It is available on the internet.) I am grateful to the authors that shared it with me. Although I feel strongly that they missed the mark in interpretation, I can appreciate the time they spent in laying out their position and rallying people around it. I wish I could be more positive about their results. The guide is organized around four “key themes,” which supposedly “define” the park:

- Key Theme 1 – The huge granite mountains of the Cairngorms National Park are unique. Their influence has shaped the natural heritage, people, landscapes and culture around them.

- Key Theme 2 – The Cairngorms National Park is made up of a unique mosaic of habitats of very high quality, and exceptional size and scale. It is a stronghold for British wildlife, including many of the UK’s rare and endangered species, and those at the limit of their range.

- Key Theme 3 – The Park is a rich cultural landscape. Separated by the great bulk of the mountains, different areas have their own distinct identity and cultural traditions, but they share deep connections to the same environments. The park is a place of ‘Mountain folk’ and ‘Forest folk’.

- Key Theme 4 – The park is a place with a sense of wildness and space at its heart, and it inspires passion both in those who live here and those who visit.

Read those statements again. Do they really “define the park’s coherent character” as claimed? Or do they just present some general attributes? If we drop a few landmark words from these statements – granite, Cairngorms National Park, British, and the UK – they could apply to numerous other mountainous places around the world, hardly expressions of the uniqueness asserted. Nor do these generalized conclusions appear to capture the essence of the place. They feel more like headings for a tourism brochure than expressions of essence. Remember, the first “password question” for an interpretive designer is “where’s the process?”  Certainly, that question would have propelled this guide in a different direction.

Certainly, that question would have propelled this guide in a different direction.

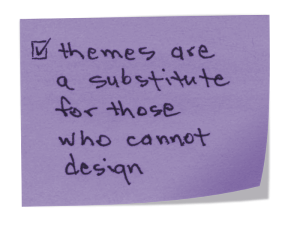

It is not unusual in our media‑driven world to find people adopting the current parlance of their field and using it to spice up their rhetoric, even before they have had a chance to determine where they are going. But the relatively new field of interpretation seems to be awash in this kind of imprecision. In one sentence alone at the beginning of the guide, themes are referred to as “big ideas,” or “take‑home messages,” or “impressions” people will tell their friends. It’s a great example of the confusing state of affairs even experienced people find themselves in these days when trying to come up with an interpretive plan. On the next page, the guide adds: “we need to share a sense of the stories that define it” (without giving the reader any sense of what those might be), and in the very next sentence, says “we also need to use those stories as themes.” Whew!

There you have it. Themes are big ideas, take‑home messages, impressions, and stories all rolled into one interpretive wrap. I trust the problem is becoming clear. Did we leave anything out of this pastiche? What about the “key concepts” mentioned in the Foreword, that pop up suddenly once more at the end, or are those synonymous with “sub‑themes” at that point?

This is Interpretive Befuddlement 101. For many, it could serve as the introductory course in the field of interpretation today. We should avoid faulting the guide’s authors for this, especially since economic development and management may have been emphasized in the brief they were given for preparing their guide. They have just taken what the field espouses and extended it into their setting, but sometimes stretching something out reveals its inherent weaknesses most clearly. Here’s an interpretive truism: When the ends are so broad as to be almost saccharine, the means often become the ends by default.

Let’s see if we have this next part right. The title of the guide is “Sharing the Stories of the Cairngorms National Park.” A story is an account. There must be no end to the number of “accounts” in the Cairngorms, and since there is no criteria for selecting from among them, almost any of the myriad possible accounts of life in the Cairngorms could be linked to the broad statements that make up the four “themes.” So if those involved in visitor services at some level, just select one of them and “link” it verbally to one of the key “themes,” their job is done? They are interpreting? Does the “means” of storytelling then become the “ends” of interpreting?

Let’s see if we have this next part right. The title of the guide is “Sharing the Stories of the Cairngorms National Park.” A story is an account. There must be no end to the number of “accounts” in the Cairngorms, and since there is no criteria for selecting from among them, almost any of the myriad possible accounts of life in the Cairngorms could be linked to the broad statements that make up the four “themes.” So if those involved in visitor services at some level, just select one of them and “link” it verbally to one of the key “themes,” their job is done? They are interpreting? Does the “means” of storytelling then become the “ends” of interpreting?

The emphasis throughout the guide is on giving people a chance to find their own connection to the place, which effectively absolves everyone of any accountability and places the site in the realm of shopping malls and reference libraries. People just wander around looking for something on their own; something which will catch their eye or engage their attention. The guide states up-front that it is not about “presenting” the park, and later suggests that doing so would detract from the authenticity people seek. Doesn’t that sound like a rather slick rationale for not doing the job? It’s the sort of strategy some university professors in other fields are fond of employing; one suspects because it saves them from having to do the really tough work themselves. And if “authentic” experience is experience without genuine interpretation, then we can go to the window and wave goodbye to our profession.

The Cairngorms guide includes some sample “starting points” for each of its key themes, but in interpretive design we are not interested in starting points until we know the ending points. Specifically, what do we want visitors to take home about a place in their head, heart, hands, and stomach? It’s difficult to design ways to enrich experience in service of mission without knowing such outcomes.

This guide, albeit unknowingly, provides an excellent illustration of why themes are such a problem in interpretation. A theme is the subject of a work. It is something being discussed or represented, like spring, friendship, or a vacation. When you take a “subject” for your outcomes, you don’t have to do anything specifically to reach it. You create your destination as you go. In interpretation this means that anything you discuss or represent is accepted as long as you tie it, however tenuously, to your subject. In current interpretive dogma they refer to these connections as “links.” In the guide, they appear to be little more than references to the broad statements identified as themes.

Let’s wrap this up. The Cairngorms guide to interpretive planning is based on a do-it-yourself strategy. Local entrepreneurs and businesses in the park are to “link” the “stories” they choose to tell to one of the “themes” identified, while giving the visitors a “chance to find their own links.” This is interpretation by default, not design. It may be an adequate branding strategy, and could support an interpretive design in many ways, but since there are no identifiable outcomes, it becomes merely a market umbrella for everyone to huddle beneath while selling their wares, like an antique mall or exhibit hall.

At the end of the guide, the novice “interpreters” culled from all those serving visitors are encouraged to take a sheet of paper, write one of the key themes in the center of the page, then jot down around it features of their work or site that could “link” to it. That’s about all the help the guide provides on developing links. There is a sample page for this exercise, and another page of random ideas – the kind of thing “brainstorming” produces – but like the “starting points,” it’s all so elementary and rambling as to be almost useless for interpretive design.

In one of the case study vignettes included in the plan, a local wildlife guide, David Newland, says: “We all need to work together to help people get the best experience of the park.” Good on ya, David. But what characterizes such an experience? How about a couple of examples? That would have been a good “starting point” for preparing this guide. From there the team could have teased out some elements of the Cairngorms language of place (sensory, perceptual, visceral) and begun identifying some clear outcomes for visitors.

There’s no doubt that all those who worked on the guide had the best interests of the place at heart, but the field of interpretation itself led them into this befuddling labyrinth. I hope they can find their way out. I have been in the Cairngorms, and they really are a special place on Earth.

Copyright © 2010 The Insitute for Earth Education